Low and no-alcohol is now the fastest-growing segment in UK beer, up over 30% in Q1 2025 vs. the same period in 2024. And it’s not just for Dry January: BBPA data shows June and July are actually the biggest months for low-alcohol sales, with last summer estimated to hit record highs.

But brewing low alcohol beer is tough, which is why sometimes it can be helpful to get some advice from the experts. The blog post below is based on a webinar given by Andrew Paterson, Technical Sales at Lallemand Brewing. Andy draws on a wealth of brewing experience from his time at Dark Star Brewing Co., and has become Lallemand’s de-facto oracle on all things No and Low Alcohol Brewing. Over to you, Andy.

What is Low Alcohol Beer?

Low alcohol beer has shifted from a niche product to a mainstream trend, driven by health-conscious consumers and changing drinking habits. Creating a beer that delivers flavour and balance while staying under 1.2% ABV is no small feat. It requires a careful blend of science, technique and creativity.

The definition of ‘low alcohol’ varies by region. In the UK, ‘alcohol-free’ means below 0.05% ABV, which is extremely difficult to achieve using standard brewing methods. Most brewers aim for 0.5% ABV or less, which falls under the low alcohol category. It’s worth noting that beers below 1.2% ABV require nutritional labelling, including calories and sugars, a detail that is often overlooked.

How Is Low Alcohol Beer Made?

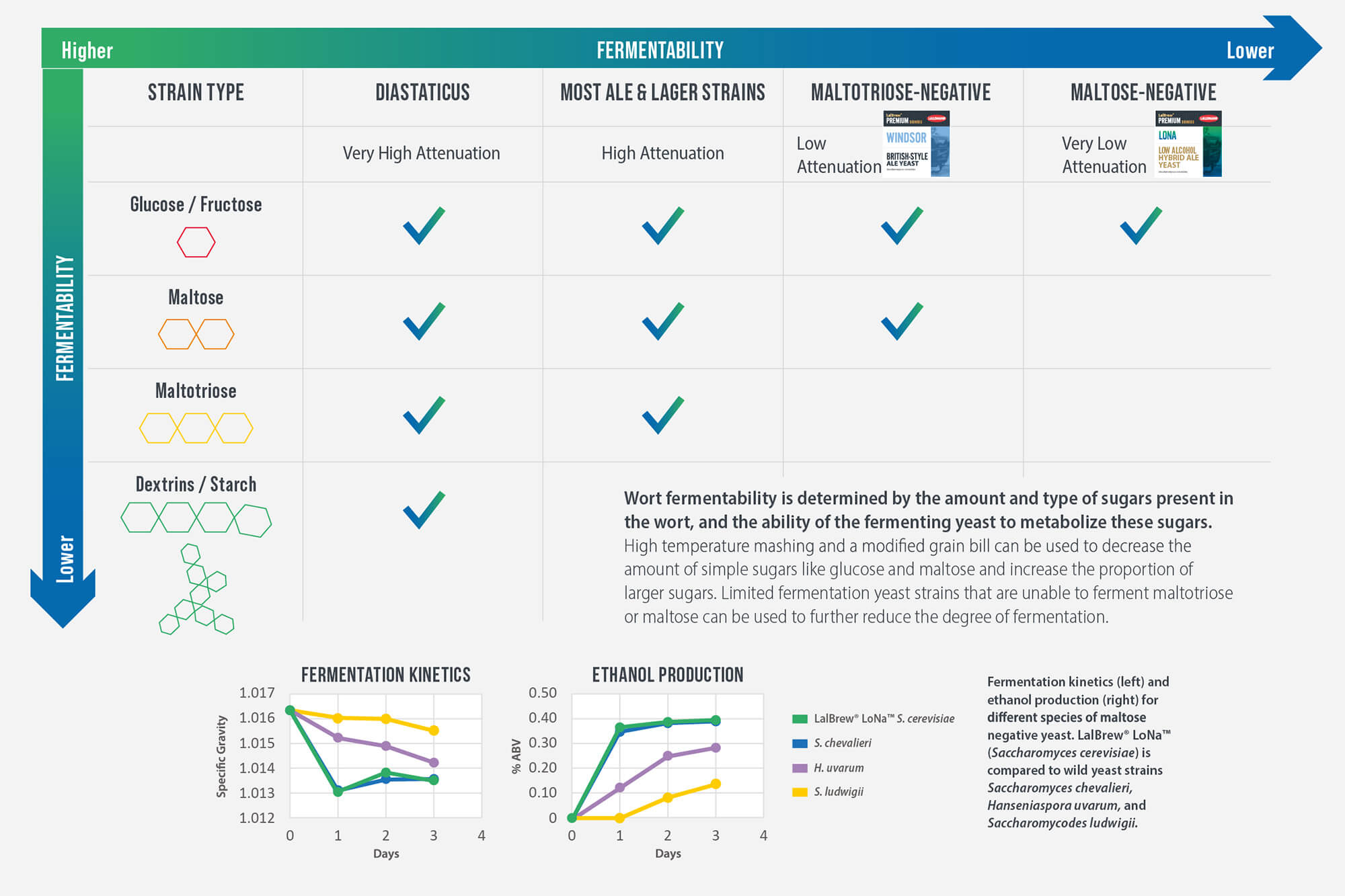

There are two main approaches: mechanical removal of alcohol or microbiological control during fermentation. Mechanical methods such as distillation and reverse osmosis remove ethanol from fully fermented beer. While effective, these techniques require specialised and expensive equipment and can strip flavour. Heat-based processes risk creating off-flavours and losing delicate aromas, even when low-pressure systems are used. Microbiological solutions take a different route. By controlling fermentation, adjusting wort composition and using yeast strains that metabolise only specific sugars like Lallemand Lallemand LalBrew® LoNa™, or LalBrew® Windsor, brewers can achieve low ABV without expensive machinery or compromising flavour.

Bristol Beer Factory's 'Clear Head' 0.5% IPA is fermented with Lallemand LalBrew® Windsor™ Ale Yeast, whilst Newbarns 'Nae' 0.5% Pale uses Lallemand LalBrew® LoNa™ Low Alcohol Hybrid Ale Yeast.

Bristol Beer Factory's 'Clear Head' 0.5% IPA is fermented with Lallemand LalBrew® Windsor™ Ale Yeast, whilst Newbarns 'Nae' 0.5% Pale uses Lallemand LalBrew® LoNa™ Low Alcohol Hybrid Ale Yeast.

The Fermentation Challenge

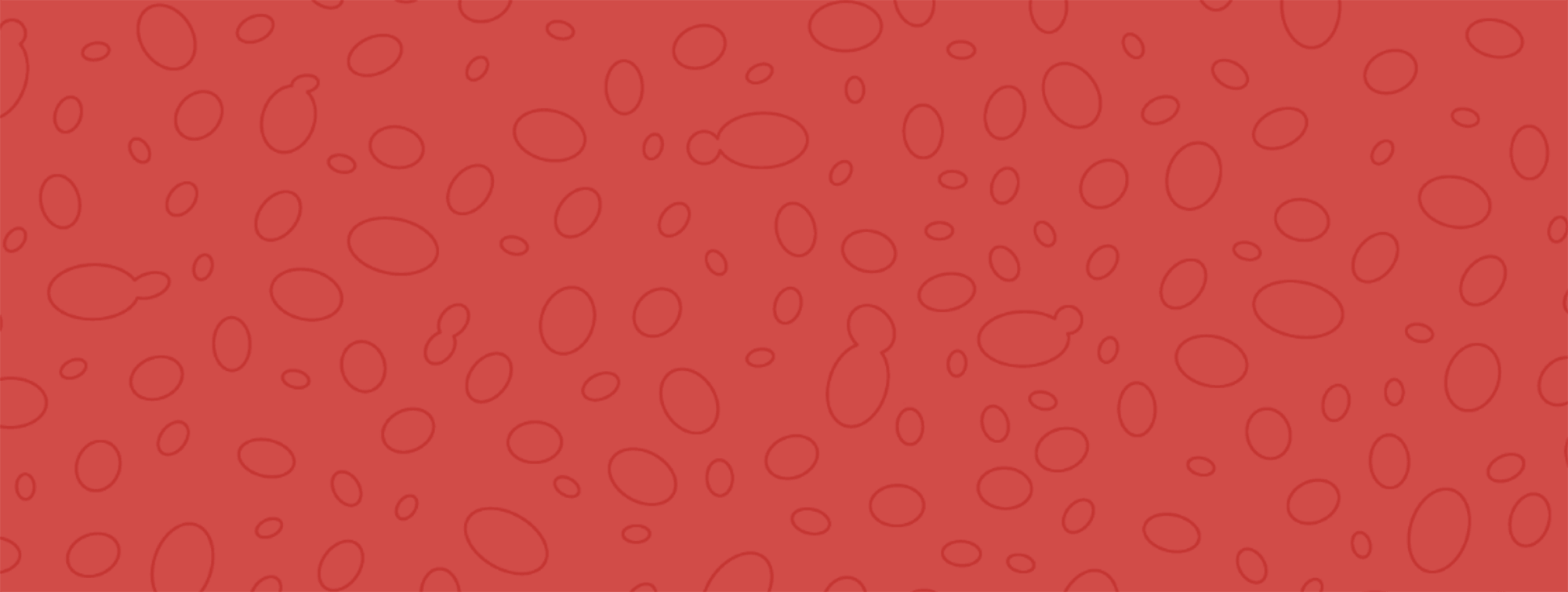

Alcohol production is fundamental to fermentation: yeast converts sugar into ethanol and carbon dioxide. To reduce ABV, brewers must either lower fermentable sugar or use yeast that only consumes certain sugars. The key sugars in a brewer’s wort are the readily fermentable glucose, maltose and maltotriose along with non-fermentable dextrins. Three strategies help achieve the goal: altering the proportions of the different sugars by hot mashing, reducing the total sugar content, and using yeast with an inability to ferment maltose or maltotriose.

Lallemand Brewing Graphic on Different Sugar Composition (Glucose, Maltose, Maltotriose & Dextrin) in Standard Beer Wort

Lallemand Brewing Graphic on Different Sugar Composition (Glucose, Maltose, Maltotriose & Dextrin) in Standard Beer Wort

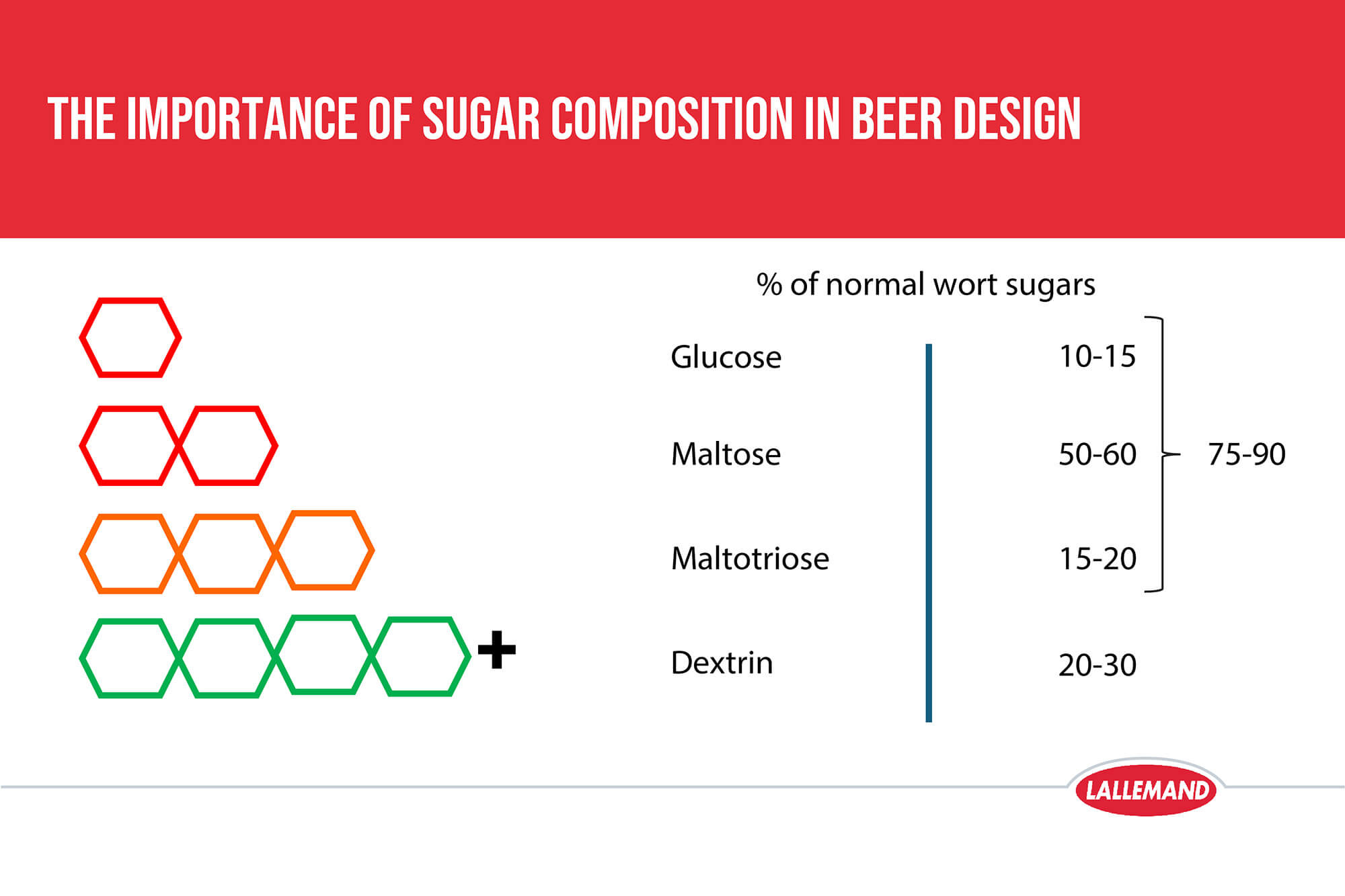

Lallemand Brewing graphic showing the Activities of Different Enzymes During Mash Conversion which influence the composition of fermentable & non-fermentable sugars in the wort.

Lallemand Brewing graphic showing the Activities of Different Enzymes During Mash Conversion which influence the composition of fermentable & non-fermentable sugars in the wort.

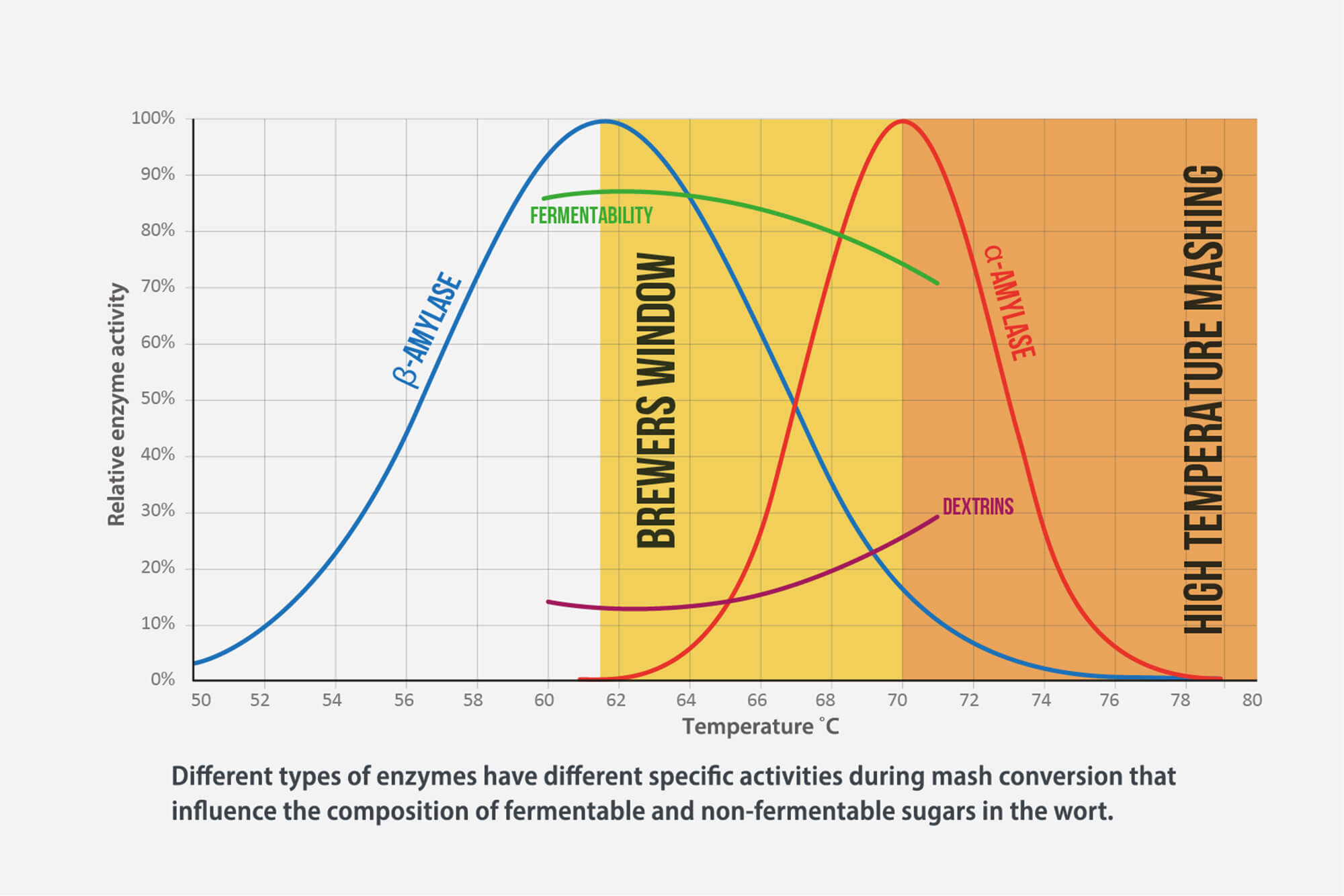

High-Temperature Mashing

Enzymes play a critical role in determining fermentability. Beta-amylase (optimum ~62°C) produces maltose, which is highly fermentable. Alpha-amylase (optimum ~70°C) degrades starch but not necessarily into fermentable sugars. By mashing at 70–75°C, brewers favour alpha-amylase, reducing maltose concentration and increasing maltotriose and dextrins. Pushing temperatures to 85–90°C further limits fermentability but introduces practical challenges such as sticky worts and poor lautering.

Lallemand Brewing Graphic showing the Effect of Different Temperatures on Sugar Concentration in Wort through High Temperature Mashing & a Comparison of Sugar Profiles Between A Typical & High Temperature Mash.

Lallemand Brewing Graphic showing the Effect of Different Temperatures on Sugar Concentration in Wort through High Temperature Mashing & a Comparison of Sugar Profiles Between A Typical & High Temperature Mash.

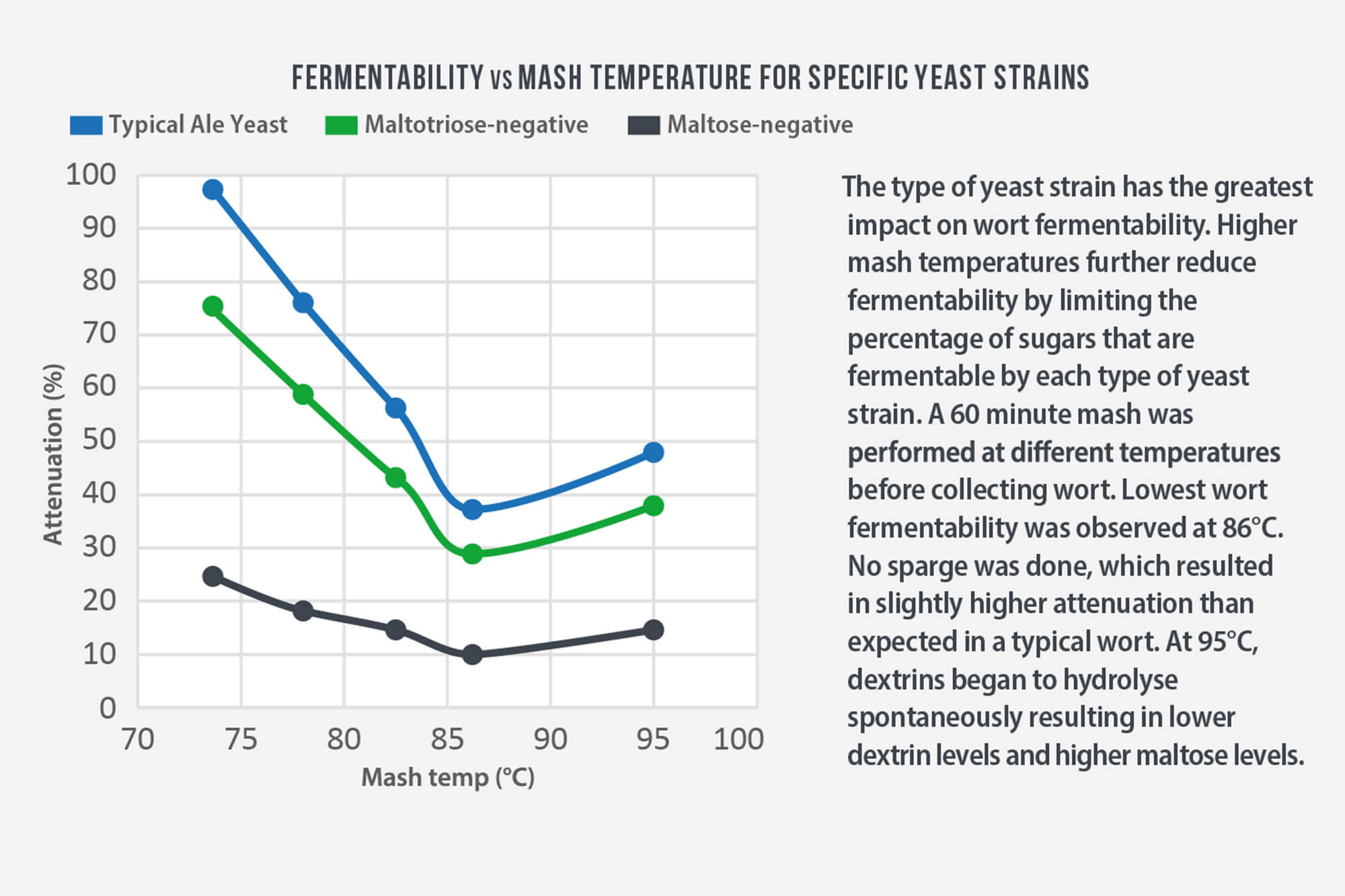

Lallemand Brewing Graphic Demonstrating the Impact of Yeast Strains on Wort Fermentability in Relation to Temperature

Lallemand Brewing Graphic Demonstrating the Impact of Yeast Strains on Wort Fermentability in Relation to Temperature

Yeast Innovation

Yeast selection is pivotal. Lallemand LalBrew® Windsor yeast, which cannot ferment maltotriose, was an early solution, reducing fermentability by 15–20%. Using Windsor in this way though would still require a very high temperature mash to limit maltose concentration – say at up to 82 degrees which comes with its own challenges. Today, Lallemand LalBrew® LoNa Low Alcohol Ale Yeast offers a more elegant approach. This hybrid strain ferments only glucose, leaving maltose and maltotriose behind. LoNa simplifies brewing by reducing the need for extreme mash temperatures and helps avoid excessive sweetness. As you’ll be able to see below, we’d still recommend a higher temperature mash than normal with LoNa for taste reasons – you’ll limit maltose production this way – not because of fermentability concerns as LoNa won’t ferment it, but because maltose is sweet and you want to limit that sweetness in your final beer to avoid that sweet ‘worty’ flavour.

Lallemand Brewing Graphic Comparison Table Demonstrating the Ability of Different Yeast Strains to Metabolise Sugars in Brewing Wort

Lallemand Brewing Graphic Comparison Table Demonstrating the Ability of Different Yeast Strains to Metabolise Sugars in Brewing Wort

Practical Low Alcohol Brewing Guidelines

- Mash at 70–75°C to limit fermentable sugars (maltose) and residual sweetness.

- Target an original gravity of 1.020 – 1.027 to prevent too much glucose being fermented, but it’s a balancing act – you also want body (and not too watery), and without excess sweetness.

- You’ll often start off with a high pH throughout the process, so you want to alter that to maintain pH at normal levels of 5.1–5.4 during mashing. A high pH can leech tannins from the mash. On run off you’ll find that the pH of your sparge drops off very quickly, so once you’ve recovered the majority of your extract rather than running through the mash tun you can actually cut the run off and top up with treated brewing liquor and then adjust pH in the boil.

- Extend the boil beyond 60 minutes to remove unwanted volatiles.

- Adjust to ≤4.6 before fermentation for microbial safety and to stop pathogen growth.

- Use LoNa yeast for best results; Windsor remains an alternative.

- Aim for a final pH of 3.9–4.2 for stability. You’ll normally see a drop of ~0.3 ph during fermentation.

- Pasteurisation is strongly recommended for product safety.

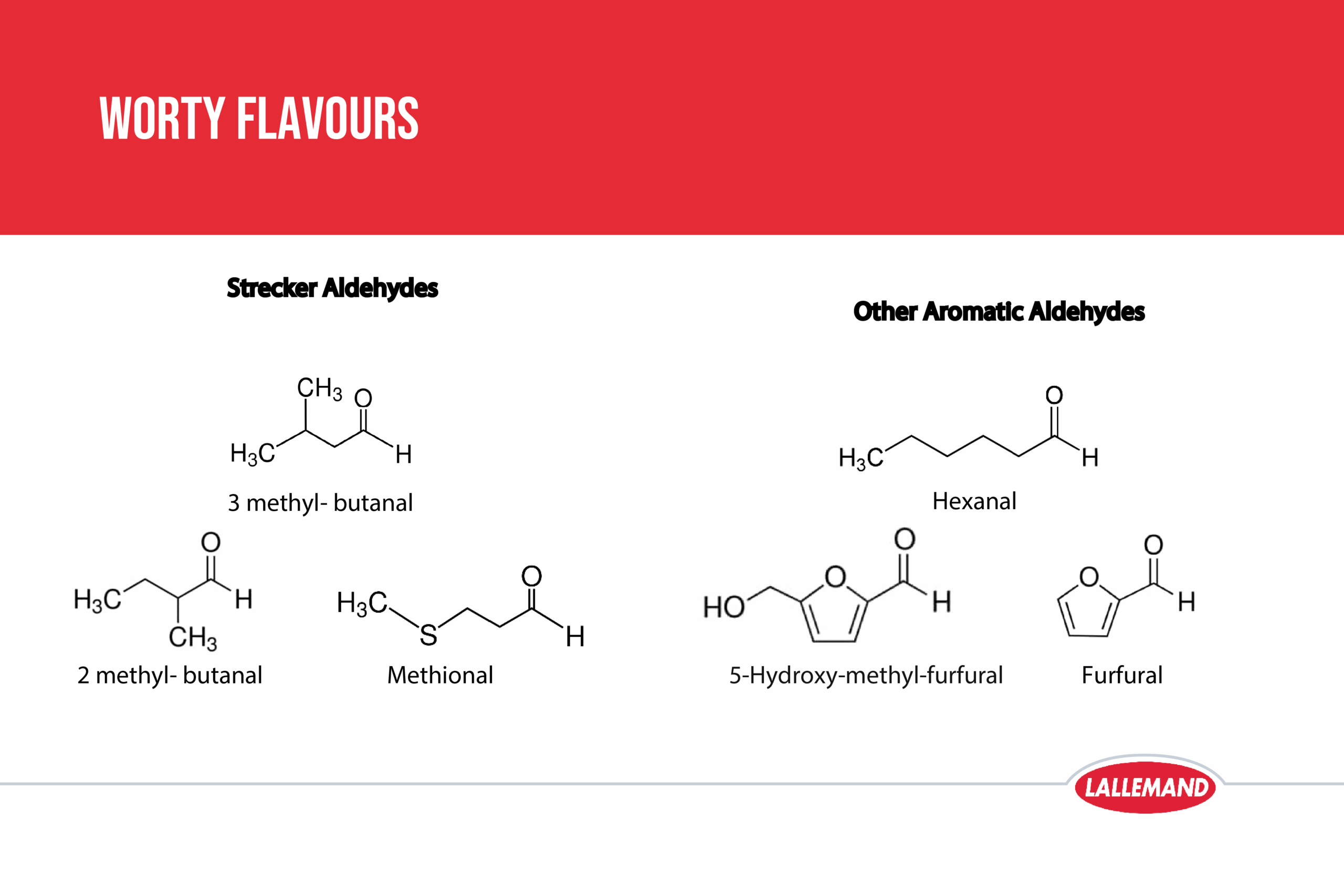

Lallemand Brewing Graphic Showing Common Aldehydes Creating Off-Flavours which Low Alcohol Beers are Especially Susceptible to.

Lallemand Brewing Graphic Showing Common Aldehydes Creating Off-Flavours which Low Alcohol Beers are Especially Susceptible to.

Malt Choices for Low Alc Brewing

Worty flavours come from aldehydes which are derived from your malt. You can limit the off-flavours from these with some simple tweaks to your malt bill.

When starting out, a simple pale malt bill gives the best chance of success. If you start to use lots of dark malts with a complex malt bill you can introduce sweetness and aldehyde-related off-flavours so best to avoid these whilst you find your feet. If you really want to brew a low alcohol stout, crystal and amber malts can be a good way to lower the pH, but again, be mindful of those aldehydes.

Acidulated malt (2–3%) helps control pH in a lighter beer. It’s probably best to steer clear of using a base malt like Maris Otter® or any complex Crystal or Munich or Vienna malts – start simple. Oats or wheat can provide useful protein and mouthfeel, and of course substituting malt for any unmalted grains also serves to reduce those ‘worty’ aldehyde flavours too.

Hops for Low Alcohol Brewing

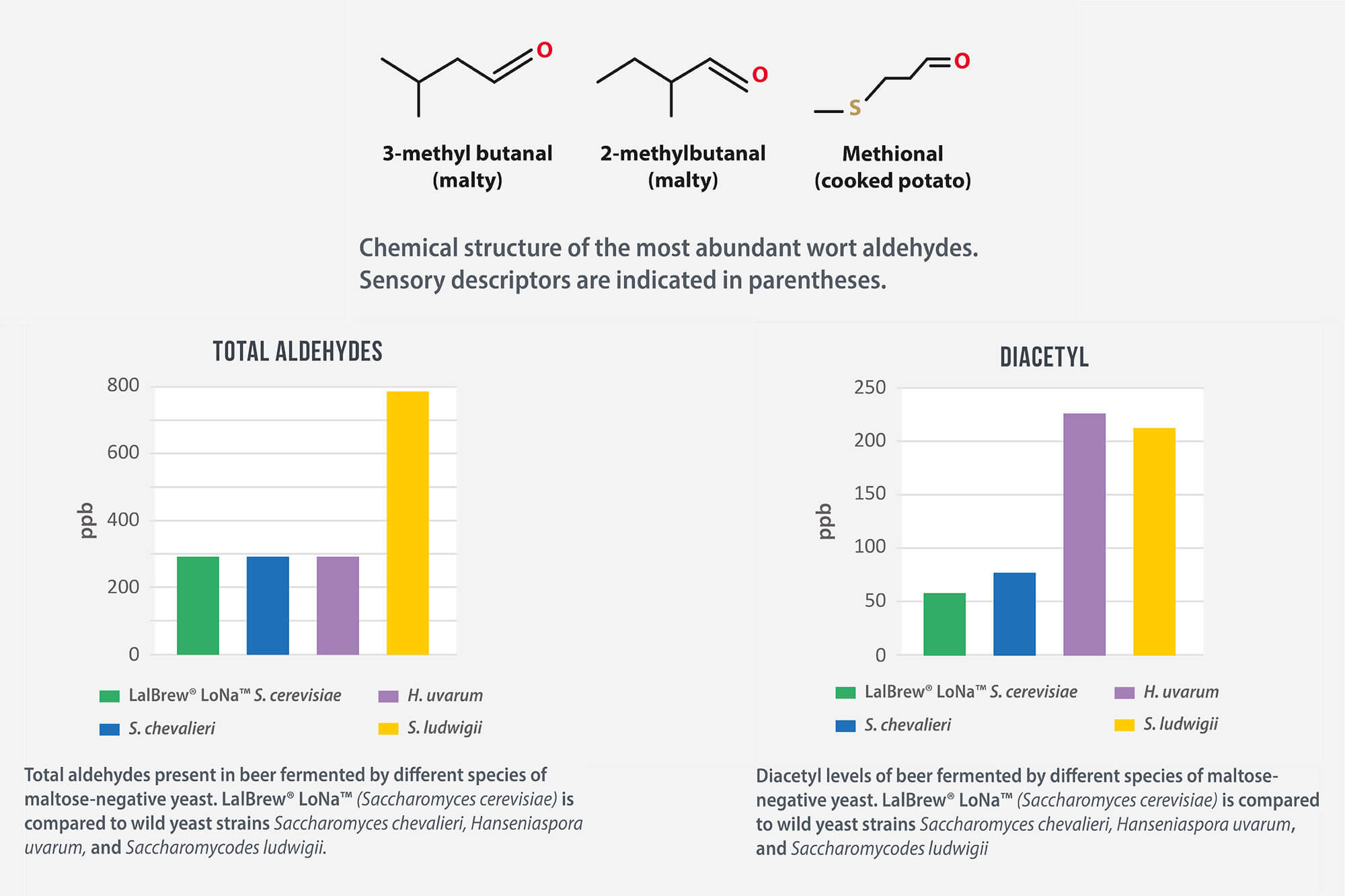

Hop strategy matters too. Keep bitterness moderate- around 15–20 IBUs for lagers – to avoid imbalance. To prevent hop creep, use advanced hop products such as cryogenic lupulin pellets or extracts, and/or restrict T90 additions to the hot side. Simple sugars like glucose can get released from larger chain dextrins in the wort by very fresh top-quality hops if you add T90s cold side and post fermentation. If you want to dry hop cold, then we recommend advanced hop products like CGX® cryogenic lupulin pellets or flowables like BarthHaas® Spectrum. Fermentations with low alcohol yeast strains are actually very short – 48-72 hours max, at which point you will need to chill your beer so you should dry hop cold. Don’t be tempted to leave the fermentation warm for longer as you’ll increase the risk of wild yeast activity. There’s no need for diacetyl rest either – low alcohol brews are such a limited fermentation that these chemicals are produced above their flavour threshold anyway.

Managing pH & Flavour

PH should be corrected at all stages of your low alcohol brewing process – mash, boil, pre-fermentation and post-fermentation. Lactic acid is a common choice for pH adjustment, but as a weak acid, when used in the larger concentrations necessary excessive use it can impart an unpleasant one-dimensional flavour. We’d recommend experimenting with different acids to adjust pH to get the results you desire. Alternatives on the weaker side would include malic (fruit sugar), phosphoric, lactic or citric acid. Stronger mineral acids (such as hydrochloric or sulphuric) add complexity and require smaller doses. It can be a good idea to take your base beer and add the acids to see which offers the best taste.

Lallemand Brewing Graphic Demonstrating Total Aldehydes & Diacetyl in Beer Fermented by Different Yeast Strains

Lallemand Brewing Graphic Demonstrating Total Aldehydes & Diacetyl in Beer Fermented by Different Yeast Strains

Preventing Off-Flavours

Low alcohol beers are prone to aldehydes, which cause sweet, ‘worty’ notes. These arise from limited fermentation and heat exposure. To mitigate:

• Minimise oxygen and thermal damage.

• Use lighter malts and antioxidant products.

• Extend boil time.

• Consider yeast derivatives like ISY Enhance to improve mouthfeel and bind harsh polyphenols.

Left Handed Giant's 'Run Free', Anarchy Brewing Co. 'Placebo Effect', Northern Monk 'Faith AF' & Bluntrock 'Zen' all pair Lallemand LalBrew® LoNa™ with AB Vickers ISY Enahnce for additional body & mouthfeel.

Left Handed Giant's 'Run Free', Anarchy Brewing Co. 'Placebo Effect', Northern Monk 'Faith AF' & Bluntrock 'Zen' all pair Lallemand LalBrew® LoNa™ with AB Vickers ISY Enahnce for additional body & mouthfeel.

Adding Extra Body & Mouthfeel to Low Alcohol Beers

As well as binding harsh polyphenols, AB Vickers ISY Enhance can be used in a similar way to maltodextrin or lactose. As an inactivated specific yeast autolysate, it adds extra body and mouthfeel to beer by binding sugars and polyphenols, and is easy to dose at a rate of around 20-60g/hl ISY in low alcohol beers, (and at the lower end of that scale for low alcohol lagers specifically). As a yeast, it does have a distinct ‘yeasty’ aroma, which can be easily overcome if added hot side to beer in order to ‘flash off’ the aroma.

Dealing with Head Retention Issues in Low Alcohol Beer

You can take steps to improve head retention with AB Vickers Foamaid PGA, and BarthHaas® Tetrahop Gold which are both available in Ireland through Loughran Brewers Select. It should be noted that PGA is an e number (e405) and so should be labelled as such. Hop Extracts like Tetrahop Gold are produced from CO2 hop extracts.

Stabilisation and Safety

Because low alcohol beers lack ethanol’s natural antimicrobial effect, they are more vulnerable to spoilage. The CO2 content in beer goes some way to mitigating this, but we still recommend stabilisation.

The best solutions for stabilisation are tunnel pasteurisation for packaged beer – we’d call this the ‘gold standard’ – and would generally recommend 40-60 PUs for low alcohol beer although you should always seek advice. Flash pasteurisation is a good option for keg beer, as well as sterile filtration. Both these solutions do carry with them the risk of contamination at the filling step unless you are using a sterile fill line. Shredder™ is also new pasteurization tech which uses structures to ‘rip apart’ cell organisms, and looks and operates a little like a filter. It’s very new to the market, so we’ll watch its performance with great interest.

Chemical stabilisers approved in the EU under very specific circumstances which may not be applicable to your beer include sulphites (up to 20 mg/L), sodium benzoate and sorbic acid. Glycolipids (like Nagardo) are approved in the EU, but are still in the consultation phase in UK legislation.

We recommend reading more on studies into beer pasteurisation, such as those below by Grzegorz Rachon et al.

Draft Beer Dispense Challenges

Serving low alcohol beer on draught introduces extra risk due to open systems and variable hygiene. Contamination from the line itself is a great concern for low alcohol beer. Dispense your beer through accounts and pubs you trust, and aim to train bar staff and cellar managers as well as audit the venues serving your low alcohol beer. Solutions include rapid turnover, cold storage and innovative dispense systems such as Heineken Blade or BeerFlux, which eliminate long lines and reduce contamination risk. For smaller scale independent breweries and venues, this can mean that one way kegs like KeyKegs with a short run and direct draw to the bar (or even an under-counter KeyKeg) are a viable option. Another product potentially worth investigating is Micromatic’s FlexiDraft™ system which utilises a one-way disposable beer line.

Final Thoughts

Brewing low alcohol beer is a balancing act. Success depends on controlling fermentable sugar, selecting the right yeast, managing pH, judicious use of brewing aids, and ensuring microbial stability. While mechanical methods exist, microbiological solutions like LoNa yeast offer simplicity and flavour retention. Pasteurisation remains essential for safety, and thoughtful ingredient choices with the right malts, adjuncts, and advanced hop products will prevent off-flavours and maintain drinkability, allowing you to create superb low alcohol beers all year around!

Check out the dedicated Low Alcohol Brewing page resource for all the ingredients you need to brew great low alcohol beers. There’s also the Lallemand NABLAB no and low alcohol brewing best practices doc which is full of useful info too.

Need specific, tailored advice, or specific questions answered? Contact us and we can help, as well as put you in touch with the experts from Lallemand Brewing too!